- January 18, 2024

Integrated Closure Planning for the Reemergence of Uranium Mining

At the United Nations COP28, key leaders from the United States, Canada, France, Japan, and the United Kingdom, pledged $4.2 billion in investments over the next three years to boost global nuclear energy supply and enhance uranium capacity for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 (U.S. Department of Energy, 2023).

The reemergence of uranium demand is also reflected in NexGen Energy Ltd. gaining approval through the Environmental Assessment Act of Saskatchewan for a greenfield uranium project (Dayal, 2023) and Consolidated Uranium’s re-opening of an underground uranium mine in Utah (GlobeNewswire, 2023).

With uranium reemerging as a significant global resource, responsible extraction practices and progressive closure planning have become essential focal points to mitigate potential impacts. In this month’s Conversation on Closure, we examine some key considerations when it comes to comprehensive integrated closure plans, ensuring a responsible approach to the revival of uranium mines with the potential to leave positive legacies.

Uranium Mining: Understanding the Commodification and Availability of Uranium

Uranium, a critical metal element, has several important applications in different industries, including medicine for treatments of certain types of cancer and agriculture for soil sterilization and pest management (Encore Energy, 2022). However, uranium is still most commonly known for its use as a fissionable material to produce fuel to generate energy (Commodity, 2023).

Uranium production employs various recovery and extraction methods, such as open-pit, underground mining, and in-situ leaching (ISL) (Commodity, 2023). Australia and Canada, with 28% and 10% of identified recoverable uranium resources respectively, employ open-pit and underground techniques (World Nuclear Association, 2023).

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)(2010) emphasizes the need for a balanced approach in the development of new uranium mines, with best practice principles applied through all phases of the mining lifecycle, inclusive of post-closure stewardship.

Key Challenges Associated with Uranium Mining

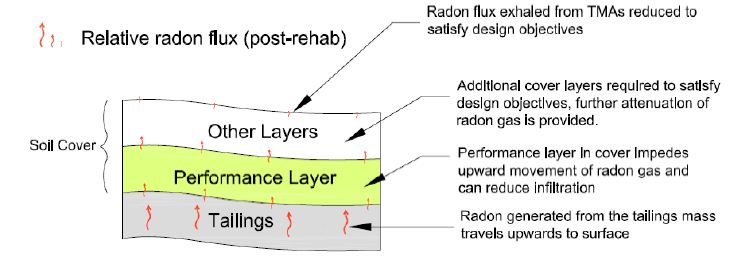

Uranium mines can involve inherent risks, particularly with radiological contamination being an elevated concern (Center for Biological Diversity, n.d.). Although uranium itself is not very radioactive, the mined ore and the tailings produced contain more radioactive decay products, such as radium (World Nuclear Association, 2017). As one of radium’s natural decay products is radon gas, uranium mining operations follow strict health standards for exposure (World Nuclear Association, 2017). Similar considerations are required when designing for closure. For example, soil cover systems for a uranium mine tailings storage facility may also include low-permeability layers, materials with complex pore spaces, and saturated finer-grain layers to manage mobilization of radon gas emitting from the tailings (Gunsinger et al., 2013).

Figure 1: A simplified soil cover profile (Gunsinger et al., 2013).

Integrated Planning to Ensure Responsible Closure of Uranium Mines

Like most mining operations for other commodities, uranium mining requires careful consideration and a proactive approach to closure, ensuring mitigation of environmental and social impacts, while thinking of ‘closure’ as an activity, or ‘tool’ to achieve land use and closure objectives.

Community engagement is an essential aspect of closure planning. Engaging with Indigenous rightsholders and community members establishes transparent communication channels, fosters mutual understanding, addresses concerns, and facilitates the integration of local perspectives into mining operations and the returning land use vision.

- At the Rum Jungle mine site, a copper and uranium mine located in Northern Territory, Australia, the Northern Territory Government has been committed to generating direct and indirect job on-site opportunities for the Kungarakan and Warai people, who are the Traditional Owners of the land where the site is located (Northern Territory Government, 2023). The community engagement initiatives at the Rum Jungle mine site highlight the Northern Territory Government’s commitment to actively involve and collaborate with Indigenous rightsholders.

Mitigating potential impacts is also critical for responsible uranium mining. This can involve progressive closure, which entails a phased approach to mine closure, allowing for reclamation and remediation of disturbed areas concurrently with ongoing operations This not only reduces liability during operations but also aids in the seamless transition of mining sites into sustainable, post-extraction landscapes by reducing closure work nearing the end of the mine’s lifecycle (APEC Mining Task Force, 2018).

- Surrounded by the Kakadu National Park in Northern Territory, Australia, Ranger Uranium Mine is committed to restoring the land to its rightful custodians, the Mirarr Traditional Owners. Since the 1990s, the Ranger project has been actively involved in the ongoing rehabilitation of the area (Minister for Resources and Minister for Northern Australia, 2022). In 2022, the Minister for Resources and Northern Australia introduced a parliamentary bill, granting legislative authority for the progressive closure of the site (Minister for Resources and Minister for Northern Australia, 2022). This legal framework empowers the return of rehabilitated zones to Traditional Owners, facilitating a smooth transition for relinquishment in the future.

Furthermore, long-term monitoring plays a crucial role in ensuring the effectiveness of environmental mitigation measures. Continuous surveillance ensures that the site attains satisfactory environmental conditions such as physical stability, surface water and groundwater quality, biodiversity, and other closure objectives

- The Cluff Lake Uranium Mine in Northern Saskatchewan placed a significant emphasis on monitoring environmental effects. With continuous monitoring and assessment of decommissioning efforts, the site demonstrates strong environmental performance and allows access for traditional activities such as fishing, trapping, and hunting (Moulding & McGuire, 2023; Orano Group, n.d.). The relinquishment of Cluff Lake Uranium Mine serves as a “prime example of responsible resource development” (Orano Group, n.d.).

Okane’s Approach

Planning for the closure of uranium mines requires unique technical expertise. We have worked with several notable uranium sites around the world developing effective closure designs that manage risk, and facilitate collaborative engagement with impacted communities. These sites have ranged from greenfield projects to operating mines, and legacy facilities either abandoned or under care and maintenance. Okane champions an interdisciplinary approach to navigate the complexities of planning for the closure of uranium mine sites.

Our dedicated team of geoscientists and geochemists conducts studies on water management to proactively minimize potential radiological risks from uranium mining through a focused approach on source term by characterizing and assessing radiological hazards. Our team then interprets these geochemical studies and leverages the results to develop appropriate management strategies required to handle those hazards.

Additionally, our ecologists ensure that land rehabilitation efforts and monitoring systems are tailored to meet the specific needs of each site. Through frameworks such as the Western Australian Biodiversity Science Institute’s ecological completion criteria and using environmental aerial surveying and reporting tools, we assess the suitability for vegetation.

Guided by our Roadmap to Closure and commitment to health and safety, we work with our clients to develop integrated mine closure plans that consider environmental, social, and financial impacts, to achieve closure that leaves a positive long-term legacy, while providing the critical metals and minerals we need for a reliable nuclear energy supply chain.

References

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Mining Task Force. (2018). Mine closure checklist for governments. https://www.igfmining.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/218_MTF_Mine-Closure_Checklist-for-Governments-1.pdf

Center for Biological Diversity. (n.d.). Uranium. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/public_lands/energy/dirty_energy_development/uranium/index.html

Commodity.com. (2023). Uranium in 2024: A guide to the commodity’s price, value, and uses. The Essential Guide. https://commodity.com/energy/uranium/#Why_Is_Uranium_Valuable

Dayal, P. (2023). Sask. government approval brings new biggest uranium project in Canada closer to reality. CBC Canada. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/sask-to-get-the-biggest-uranium-mining-project-1.7042371

Encore Energy. (2022). A useful element: Uranium and its various applications. https://encoreuranium.com/uncategorized/uranium-and-its-various-applications/

GlobeNewswire. (2023). Consolidated uranium commences drilling and reopening of the underground at the Tony M Mine. https://financialpost.com/globe-newswire/consolidated-uranium-commences-drilling-and-reopening-of-the-underground-at-the-tony-m-mine

Gunsinger, M. R., Andruchow, B. & Becker, E. (2013). Closure of uranium tailings facilities: environmental considerations, regulatory framework and conceptual options. Mine Closure 2013: Proceedings of the Eighth International Seminar on Mine Closure, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Cornwall, pp. 149-157, https://doi.org/10.36487/ACG_rep/1352_13_Gunsinger.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). (2010). Best practice in environmental management of uranium mining. IAEA Nuclear Energy Series Publications. https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/Pub1406_web.pdf

Minister for Resources and Minister for Northern Australia. (2022). Securing the Ranger mine clean up and return to traditional owners [Media release]. https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/king/media-releases/securing-ranger-mine-clean-and-return-traditional-owners.

Moulding, T. & McGuire, C. (2023). Regulatory oversight for Cluff Lake mine reclamation, closure, and long-term management. BC ML/ARD Conference Presentations. https://bc-mlard.ca/files/presentations/2023-2-MOULDING-MCGUIRE-regulatory-oversight-cluff-lake-mine.pdf

Northern Territory Government. (2023). Rum Jungle rehabilitation plan: Draft environmental impact statement (Part 1). Northern Territory Government Australia. https://nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/1100844/eis-part-1.pdf

Nuclear Energy Agency. (2023). Maximizing uranium mining’s social and economic benefits: a guide for stakeholders. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_72776/maximising-uranium-mining-s-social-and-economic-benefits-a-guide-for-stakeholders?details=true

Orano Group. (n.d.). Decommissioning. https://www.orano.group/canada/en/our-uranium-expertise/decommissioning

U.S. Department of Energy. (2023). At COP28, U.S., Canada, France, Japan, and UK announce plans to mobilize $4.2 billion for reliable global nuclear energy supply chain. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/articles/cop28-us-canada-france-japan-and-uk-announce-plans-mobilize-42-billion-reliable-global

World Nuclear Association. (2017). Environmental aspects of uranium mining. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/mining-of-uranium/environmental-aspects-of-uranium-mining.aspx

World Nuclear Association. (2023). Supply of uranium. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.aspx