- October 17, 2024

Adaptive Management Frameworks for Integrated Mine Closure

Many mine sites worldwide face areas of uncertainty, which stem from the lack of knowledge or understanding of the mechanisms that may influence how a site operates in the long term. These uncertainties can pose significant risks to projects, such as long-term water quality impacts from potential acid-generating mine rock or erosion and slope failure due to geotechnically unstable designs. These risks affect decision-making and outcomes throughout the entire lifecycle—from exploration and operation through to closure and post-closure.

Implementing an adaptive management framework addresses these risks by providing an iterative approach to assess and adjust strategies based on developing information and conditions. This framework empowers decision-makers to effectively navigate uncertainties, ultimately enhancing the sustainability and success of mine closure efforts.

A common challenge faced by many site owners is the confusion between adaptive management plans (AMPs) and trigger action response plans (TARPs) due to overlapping actions in both risk-based management plans. In this article, we will explore how to develop an effective AMP and highlight the key distinctions between adaptive management planning and TARPs.

Adaptive Management Framework

Adaptive management planning is an approach that allows continual assessment and management of risks and uncertainties in a project. Adaptive management approaches help improve project knowledge over time and enable decision-makers to evaluate and address risks and uncertainties while considering and pursuing multiple decision alternatives until the best one is identified.

Understanding risks and uncertainties according to ISO 31000:2009:

- Risks: A risk refers to the effect of uncertainty on objectives. It arises from incomplete knowledge of events or circumstances that influence decision-making. Risk is typically calculated by multiplying likelihood by consequence.

- Uncertainties: Uncertainty refers to a (partial) state or situation where there is a lack of information, understanding, or knowledge about an event, its consequences, or its likelihood.

For example, an uncertainty might be the volume of potential acid-generating mine rock that needs to be managed at a mine site, which could pose a risk to water quality.

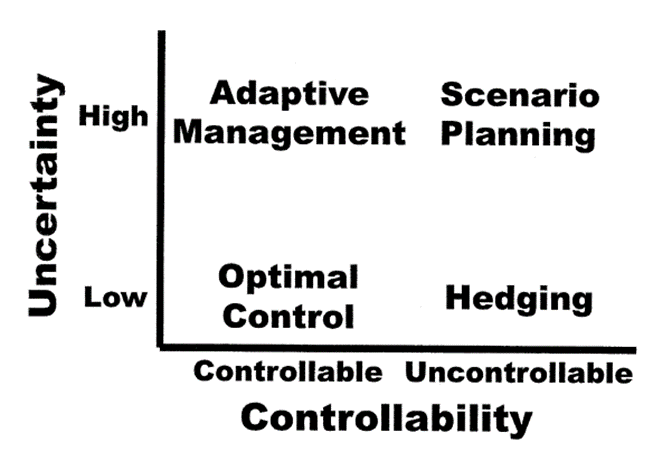

An AMP does not contain prescriptive measures for addressing a specific risk or uncertainty; it is a cycle that provides mine operators with various options to follow and implement if monitoring data and results do not mitigate the identified risk or uncertainty. This cycle consists of six steps (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The six steps to an adaptive management cycle. Adapted from “Nyberg (1999) in the Proceedings of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resource Adaptive Management Forum (MacDonald et al., 1999)”, as cited in Crawford et al. (2005).

Developing Adaptive Management Plans

The following guidelines expand on the steps outlined in an adaptive management cycle for developing an AMP tailored to a project site:

- Assessing and defining potential concerns

The most important steps to assessing and defining potential concerns typically involve:

- Setting realistic goals for the AMP and defining what successful outcomes would look like for a specific concern.

- Developing a conceptual model that demonstrates the source or root cause, processes and transformations, and consequences or outcomes.

- Identifying risks either through risk review workshops and using tools like failure modes effects analysis (FMEA) to understand why something is a risk, its impacts, and the precedence of this risk in other projects with similar conditions (analog sites).

- Confirming if there are alternative viable management actions available to respond to changes.

- Designing the plan

Designing the AMP involves:

- Developing and stating qualitative or quantitative hypotheses.

- Identifying measurable indicators to provide objective information on the status of the problem being addressed.

- Identifying actionable threshold levels of conditions which a project can safely operate within.

- Developing a monitoring plan to assess the AMP against the identified thresholds.

- Developing timelines for monitoring, evaluations, and reporting to assess project progress and traction of the AMP objectives.

- Engaging with stakeholders, Indigenous rightsholders, and community groups

While engagement and consultation are not part of the AMP process cycle, AMPs benefit from comprehensive collaboration and engagement with subject matter experts, such as regulators, Indigenous rightsholders, community members, and stakeholders. Engagement and consultation can provide valuable feedback for consideration in the AMP.

It is important to note that engagement can occur at any point in the AMP cycle; however, at minimum, it should be conducted after the AMP plan is designed. The process, progress, and outcomes of the AMP should be transparent and clearly communicated.

- Implementing the plan

After the planning and designing phases of the AMP are completed, with acceptance from necessary subject matter experts, the next milestone is to begin the program to address the problem. Depending on the complexity of the AMP, an implementation procedure may be necessary to develop.

- Monitoring the results

Once the AMP is implemented, monitoring begins as outlined in the monitoring plan in Step 2.

- Evaluating and assessing the results

A truly adaptive plan allows for modifications to all AMP components based on the evaluation and assessment of monitoring results. The AMP should specify the frequency and methods for comparing measurement indicators to identified thresholds. This step includes evaluating whether monitoring results are on target, whether uncertainties are resolved, whether assumptions and hypotheses remain valid and whether a management decision needs to be made.

- Adjusting or discontinuing the plan

If monitoring results indicate that the uncertainty is being resolved, discontinuing the AMP may be considered. If uncertainty persists but the associated risk is minor, the plan can transition into a monitoring plan. If the AMP falls short of its objectives, informed adjustments, along with the generated data, new knowledge, and lessons learned, can be applied in the next iteration in order to meet the AMP objectives.

Adaptive Management vs. Trigger Response: What’s the Difference?

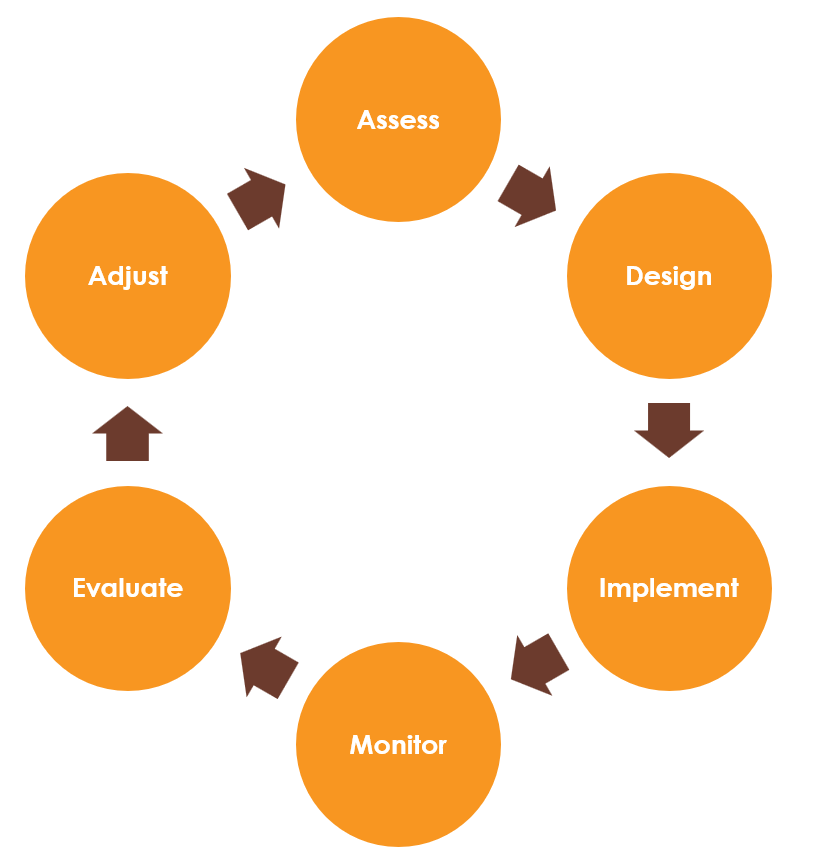

Although AMPs and trigger action response plans (TARPs) have similar requirements (critical thresholds, monitoring plans, and timelines) (Figure 2), the outcome for each is different. Adaptive management is meant to manage risk and uncertainty in a ‘learning by doing’ approach. An AMP is typically an iterative process, where the problem is revisited once there is monitoring or lab testing data available. At this stage, the level of uncertainty is also revisited. If an uncertainty has been reduced and the level of risk is within an acceptable level, then the adaptive management plan can be revised to determine whether to continue monitoring it or discontinue the plan.

In contrast, a TARP is a prescriptive tool that follows a clear approach: “If X happens, then we need to do Y.” TARPs are detailed operational plans designed to respond to changes detected through monitoring (BC MECCS, 2022). Unlike AMPs, TARPs establish explicit contingency measures based on predetermined conditions, including specific actions, assigned responsibilities, and timeframes for responding to defined changes in waste and receiving environment conditions identified through monitoring (BC MECCS, 2022).

An AMP focuses on achieving specific objectives and aims for proactive management that allows for site closure, while a TARP is invoked when these objectives are not met, necessitating a reactive measure.

Figure 2. This graphic illustrates Okane’s vision for the AMP and the relationship between the AMP (in blue) and a TARP (in yellow). The green steps represent overlapping actions for both AMPs and TARPs. While these are separate entities, they work together effectively.

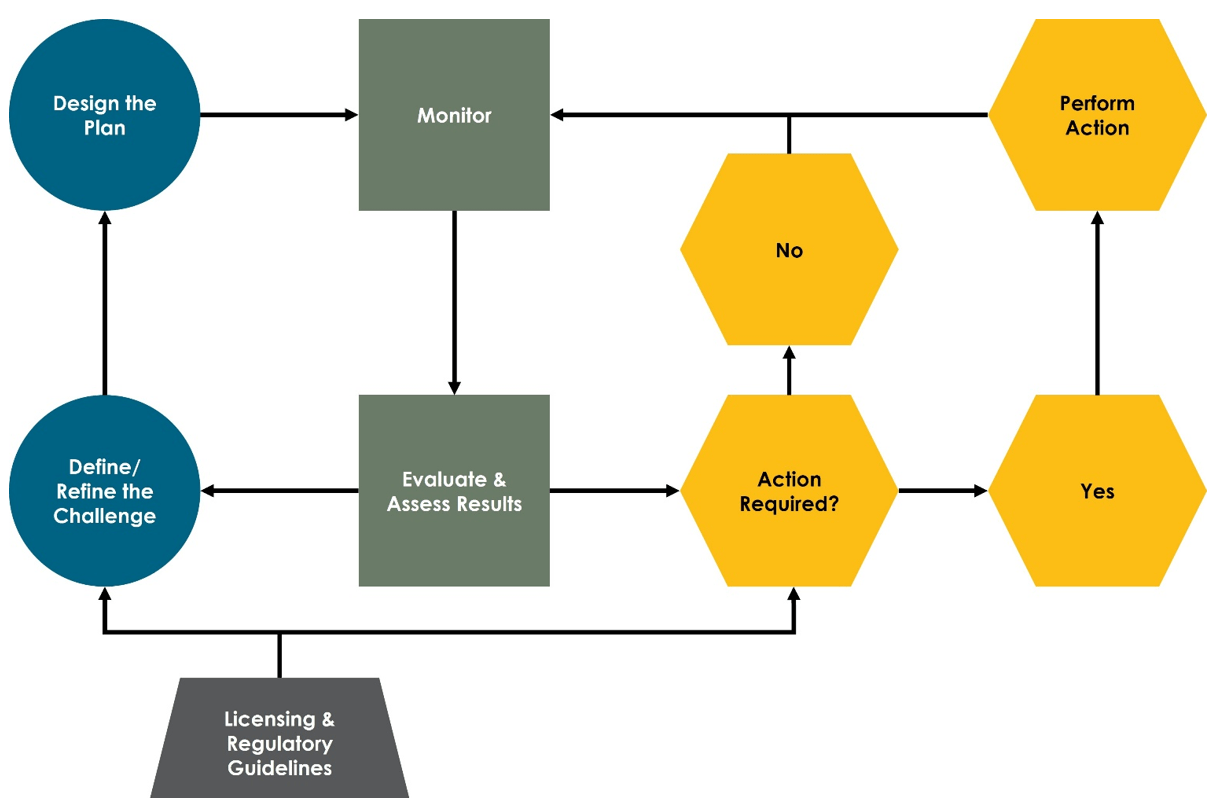

Okane’s Approach

Okane’s approach prioritizes starting early in the mine life when levels of uncertainty are high, and we have greater control over managing the uncertainties and their potential outcomes. Planning for adaptive management at the outset allows for multiple management options to be available. The role of adaptive management is to study or monitor unknowns in order to make the best long-term decisions for all parties involved on the site.

We help clients understand what “best” means when making decisions about the path forward by including all parties involved. A useful analogy for our approach is how different subject matter experts view an elephant from different perspectives, each focusing on a specific part. For instance, the trunk may resemble a snake, while the tusk may appear as a spear—much like in John Godfrey Saxe’s 1873 poem The Blind Men and the Elephant (CommonLit, 2024).

In this analogy, each subject matter expert sees only part of the elephant and may not fully understand how all parts of the elephant fit together. By bringing all subject matter experts together, Okane provides an interdisciplinary approach, fostering collaboration among experts to see the bigger picture—the entire elephant—and determine the best path forward.

Our approach to Adaptive Management and Strategic Risk Assessment takes an integrated view, considering all perspectives on risks and uncertainties to design a comprehensive plan that incorporates multiple viewpoints. Okane is involved throughout the entire process, ensuring that clients, regulators, Indigenous rightsholders, community members, and stakeholders have confidence in the AMP.

For more information on how we can help develop risk-based plans specific to your site, contact us at info@okaneconsultants.com.

References

British Columbia Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy (BC MECCS). (2022). Development and use of adaptive management plans. Retrieved from Government of British Columbia website: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/waste-management/industrial-waste/industrial-waste/mining-smelt-energy/guidance-documents/tg20_guide_to_preparing_adaptive_management_plans.pdf

CommonLit. (2024). The Blind Men and the Elephant. Available at: https://www.commonlit.org/en/texts/the-blind-men-and-the-elephant (Accessed: 03 October 2024).

Crawford, S., Matchett, S., & Reid, K. (2005, May 23—27). Decision analysis/adaptive management (DAAM) for Great Lakes fisheries: A general review and proposal [Paper presentation]. International Association for Great Lakes Research (IAGLR) 2005, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

International Organization for Standardization. (2009). Risk management—Principles and guidelines (ISO Standard No. 31000:2009). https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-1:v1:en

Peterson, G. D., Cumming, G. S., & Carpenter, S. R. (2003). Scenario planning: A tool for conservation in an uncertain world. Society for Conversation Biology, 17(2), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01491.x