- November 20, 2025

What is a Conceptual Model?

The Government of Canada has recently released Budget 2025, which introduces a series of measures aimed at strengthening the development of critical mineral projects and supply chains, particularly at upstream and midstream segments of the value chain, and accelerating near-term projects into production (Government of Canada, 2025). Under this plan, site owners have an opportunity to position themselves for further success by optimizing operations that integrate risk management, constructability, and land and water stewardship principles from pre-feasibility through to closure and post-closure.

As mine planning and closure consultants, one of the key tools we leverage to support this integration is a conceptual model. These conceptual models provide the opportunity for informed simplicity to support investment decision-making, such as Canadian Securities Administrators National Instrument 43-101 Technical reports, Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee, and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission S-K 1300 statements, project descriptions, and preliminary economic assessments. By leveraging conceptual models, site operators can develop planning, execution, and closure strategies that are transparent, backed by data and technical studies, and align project outcomes with regulatory, environmental, and investment objectives.

In our experience, many mine and closure plans tend to replicate the “successful designs” of past projects rather than adopting the design principles and processes that made those projects successful, and applying site-specific controls. This oversight often leads to designs that are “locked in” too early and based on assumptions of “what good looks like” without meaningful engagement with stakeholders and rightsholders (O’Kane, 2025). As a result, site owners miss the opportunity for site-specific, community-aligned, and regionally functional ecological outcomes. The opportunity to take advantage of the benefits of integrated and progressive mine closure during planning and operations may also be missed if closure planning only comes into focus later in the mine lifecycle.

The lack of an integrated approach can lead to unforeseen and poorly funded liabilities, such as:

- water quality issues that require long-term active management, and

- material rehandling across the site to achieve closure outcomes.

This challenge highlights the focus of this month’s Conversation on Closure, where we spotlight the importance of an integrated, conceptual closure model, one that prioritizes operational efficiency and environmental stewardship by designing with the future in mind, informed by collaboration, research, and adaptability to evolving industry standards.

What is a Conceptual Model?

A conceptual model is a tool leveraged to identify and outline the key processes occurring within a real-world system that users seek to understand or quantify (O’Kane, 2025). It is a systematic and digestible representation of how different components of a complex natural or engineered system interact. Conceptual models provide the foundation for subsequent modelling works, such as numerical, mathematical, or reactive transport modelling.

Conceptual models are regarded as the most effective and appropriate means to internally and externally communicate technical information (INAP, 2024). Incorporating thoughtful conceptual models into closure planning provides a transparent, adaptable, and communicable foundation for environmental and engineering analyses.

Why is a Conceptual Model Important?

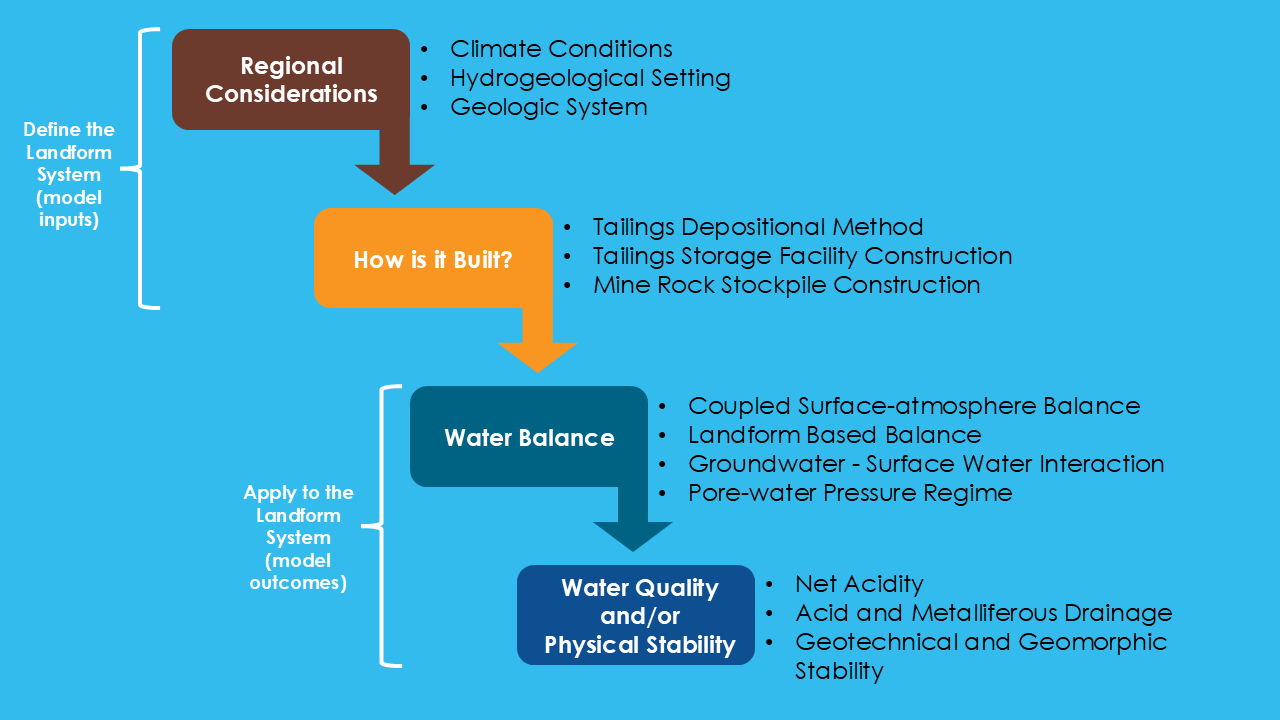

Conceptual models are important to understanding site-specific processes and controls, as well as identifying data gaps to improve model performance and reliability (O’Kane, 2025; INAP, 2017). A conceptual model integrates site and regional considerations, construction methods, water balance, physical stability, and water quality to help inform practical decision-making.

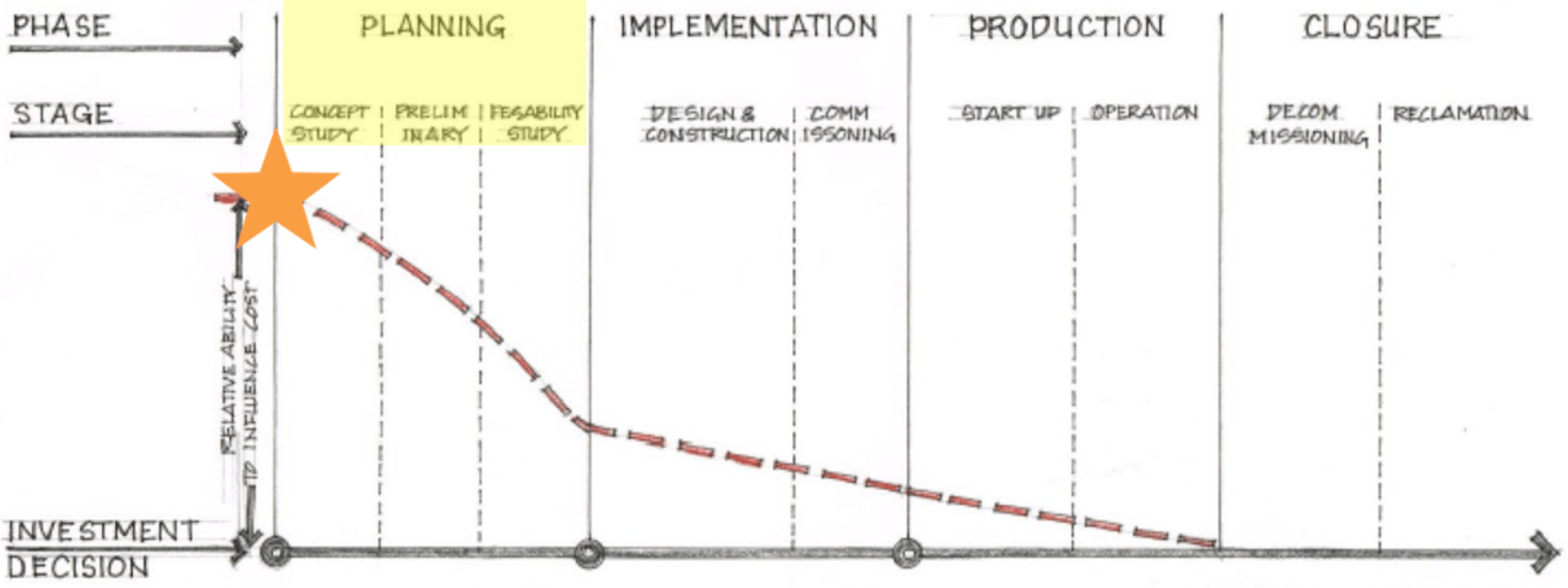

While remaining the appropriate ‘communication tool’, any conceptual model must evolve as the project matures, responding to additional information and further engineering control(s). The challenge is to not assume the importance or implementation of a specific engineering control too early in the design without deep consideration of site-specific conditions. In our experience, it can be significantly challenging to change or ‘unwind’ a design that was developed on the basis of a poorly-formed conceptual model, even at the preliminary and feasibility study stage. Therefore, we should aim to develop the conceptual model and reach alignment on it even before the preliminary and feasibility design stages (as shown in Figure 1), where there is the greatest opportunity to influence the cost of an asset’s lifecycle.

Figure 1. Relative ability to influence cost of an asset’s lifecycle (adapted from Lee (1984) and Hustrulid & Kuchta (1998), illustration by D. Shuttleworth).

Okane’s Approach

At Okane, we leverage a hierarchical framework for developing a conceptual model, which focuses on four aspects:

· regional considerations,

· how is it built (construction methods),

· water balance (including porewater pressure regime), and

· water quality and/or physical stability.

At the conceptual model stage, during the asset planning phase, the ability to influence overall project cost is at its highest (O’Kane, 2025). Since the goal is to establish a reliable conceptual model for decision-making, the conceptual model must be structured in a way that prompts questions that could support integrated planning. In essence, we need to ask “and” questions as well as “or” questions, prioritizing the former given that ”and” questions help drive sustainable and effective solutions, while “or” questions bring focus to compliant and efficient outcomes.

For example, “How do I incorporate geotechnical stability and geochemical stability into my landform design?” in addition to, or rather than, “Is geotechnical stability or geochemical stability the primary objective for the landform?”

Figure 2. The foundational components of developing a conceptual model.

Model Inputs

The conceptual model is simple but offers the opportunity to ask complex questions that lead to informed simplicity, which is transparent and easier to communicate than solely relying on complex numerical modelling results to communicate landform design and performance.

As shown in Figure 2, the conceptual model involves defining the landform system (model inputs) and then taking these inputs to apply them to the landform system (model outcomes). It is important to note that the conceptual model is hierarchical.

Regional considerations must be considered first, as they are aspects that designers can do little to nothing about. For example, site-specific climate cannot be controlled, and the geologic system “is what it is”. The hydrogeologic system is similar to regional and geologic considerations, although it can be engineered to some extent, but only with substantial effort to achieve meaningful differences.

The second aspect of the conceptual model system inputs is asking, “How is it Built?”. For all infrastructure, including mine landforms, we need to understand how it is built and how it is planned to be built, because this strongly influences how it performs. As designers, we have control over this aspect of the system input; however, within the conceptual model’s hierarchical framework, it is important that we are careful so as to not simply apply a design from another site first and then fit that design to the regional considerations. Rather, we should first consider these site-specific conditions and then develop the appropriate construction methodology.

In Figure 2, the regional considerations shown are purposefully “technical”, but within an integrated mine planning and closure planning context, the closure vision, principles, and objectives must also be incorporated as part of regional considerations, as these considerations will also influence how a landform is built.

This same hierarchical framework for conceptualizing performance can also be applied to better understand existing mine landforms as part of detailed closure planning and risk management at legacy mine sites.

Model Outcomes

It is critical to understand the landform’s water balance in the context of the site-wide water balance before predicting water quality and physical stability. Typically, when conceptualizing water quality, the geologic system’s geochemical characteristics form the basis for predicting water quality risk. However, without also considering climate conditions, the hydrogeologic system, landform construction, and water balance, these predictions can lead to significantly flawed outcomes, resulting in difficult-to-quantify or ‘hidden’ conservatism, as well as poorly recognized and underfunded liabilities.

In our experience, a common approach is to develop a ‘first pass’ water quality prediction, but this would often result in prediction outputs that are not well aligned to site-specific conditions (other than the geologic system).

The hierarchical approach to developing conceptual models requires us to consider how a landform’s water balance shifts from operational conditions to closure conditions, as the landform system will eventually evolve due to closure measures such as resloping, cover systems, and buttresses.

A key principle in developing effective conceptual models throughout the modelling process is to begin with simplicity and incrementally incorporate complexity (Barbour and Krahn, 2004). The approach presented embraces this perspective. According to our Senior Technical Advisor, Mike O’Kane, the ultimate goal is to create a model that captures “integrated and informed simplicity”, making it reliable, adaptable, and capable of supporting informed decision-making throughout the asset lifecycle.

Applying Conceptual Models for Cover System Performance

In our contribution to the ARD/AMD Source Control for Mine Rock Stockpiles Phase 3, conceptual models were developed to assess the benefits of implementing source control measures within mine rock stockpiles. The conceptual models were applied to two distinct sites, one in the Pilbara Region of Western Australia and another in western Canada.

The conceptual models applied to both sites indicated that construction methods limiting re-supply of oxygen deep within the landform could improve water quality, potentially minimizing perpetual reliance on water treatment (INAP, 2024) while also helping to optimize cover system design. At the Canadian site, water treatment could have been largely avoided, while at the Australian site, some treatment would still be required, but its duration could be substantially reduced (INAP, 2024).

No matter the stage of a mine, having complete data for every numerical modelling input is rare. This is where having a strong conceptual model is important. A conceptual model provides a clear framework to communicate assumptions, limitations, and risks, while also identifying opportunities and informing on sensitivity analyses (O’Kane, 2025), thus guiding site owners to make informed decisions with confidence.

If you’re looking to explore how we can collaborate to bring clarity and optimization to your mine and closure plans, please reach out to us at info@okaneconsultants.com.

References

Barbour, L. S., & Krahn, J. (2004). Numerical modelling – Prediction or process? Geotechnical News 22:44–52.

Government of Canada. (2025). Canada Strong Budget 2025. Retrieved from the Government of Canada website: https://budget.canada.ca/2025/report-rapport/pdf/budget-2025.pdf

Hustrulid, W.A. & Kuchta, M. (1998). Open pit mine planning and design (Vol. 2). AA Balkema, Rotterdam.

International Network for Acid Prevention (INAP). (2017). Global cover system design technical guidance document. INAP.

INAP. (2024). ARD/AMD Source control for mine rock stockpiles: Phase 3. INAP.

Lee, T. D. (1984). Planning and mine feasibility study – An owner perspective. Short Course. Mine Feasibility – Concept to Completion, Northwest Mining Association, Spokane.

O’Kane, M. (2025). Thirty years of applied unsaturated soil mechanics in the mining industry. 4th Pan-American Conference on Unsaturated Soils, Ottawa, Canada, 2025.