- September 24, 2025

What is Residual Risk?

As mine closure practitioners, we understand that even when a mine site follows the required steps in its closure and land use transition plans, not all risks are eliminated, especially those that emerge post-closure. It is important to recognize that risk does not end with the official closure of a mine. Residual risks are the ongoing risks that remain after closure, particularly those related to not achieving closure objectives, even when preventative and mitigative reclamation measures have been implemented and are performing effectively (Sanders et al., 2019).

Risks should be identified not only in relation to operational activities, water quality, and rehabilitation outcomes, but also in terms of long-term land use functionality. This complexity makes it a challenge to establish a standardized approach to managing residual risks after closure.

As highlighted by the International Geotechnical Center (2025), a strategy to establish clear objectives, monitoring performance, and working towards a principle to keep the risks “As Low As Reasonably Practicable” (ALARP) is required for the mining industry to progress towards safer, responsible, and long-term mine material and closure management.

In this month’s Conversation on Closure, Cooperative Research Centre for Transformations in Mining Economies (CRC TiME) and Okane Consultants collaborate to share expert insights on defining residual risks, and discuss the importance of managing these risks to maximize value in post-mining transitions.

Defining Residual Risks

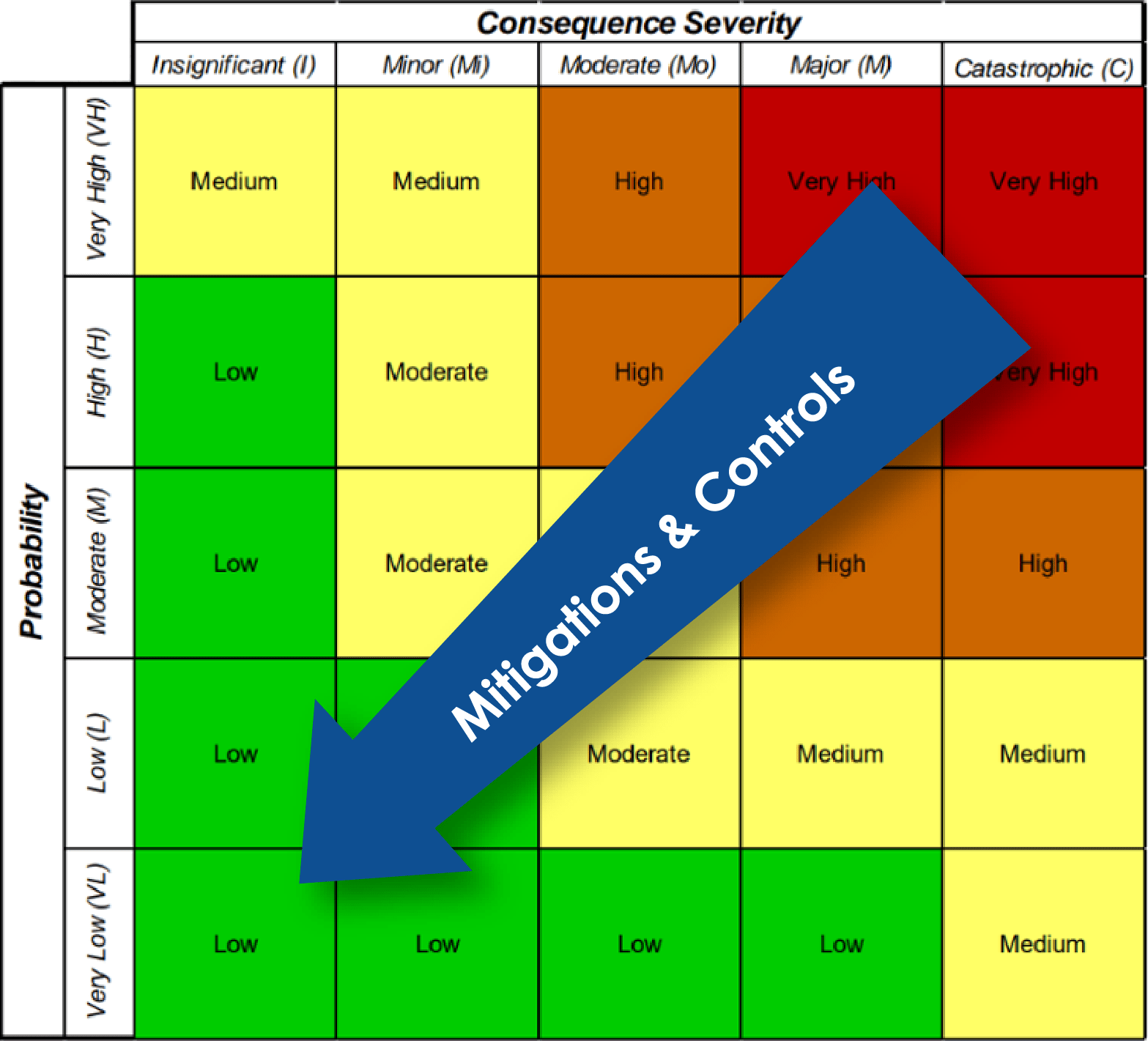

A fundamental component of mine operations involves developing a strategy for evaluating and planning for risk. The term ‘risk’ encompasses both concepts of likelihood (i.e., frequency) of an occurrence and the severity of its expected consequence.

Quantifying such occurrences is an imprecise exercise as predictive risk assessments depend on anticipating future scenarios. This uncertainty can present both an upside, manifesting as opportunities to enhance value, and a downside, the traditional conception of a risk. Both upside risks (also called opportunities) and downside risks, arising from inherent and contextual characteristics of an asset, should be considered when developing detailed risk assessments as opportunities can sometimes mitigate downside risk exposure.

Residual risk is commonly understood as the risk that remains once all mitigation actions have been taken or controls have been put in place (Figure 1). Identifying residual risks is limited by the team’s understanding of risk and ability to foresee future conditions that may occur. One challenge with the determination of risks is that the team may not know or understand all the potential risk events, or be able to fully quantify how their consequences could evolve over time.

Prioritizing Residual Risk Management for Post-Mining Transitions

Mining is a temporary land-use. Once operations have ceased, the mine site advances to closure, and the land should be evaluated for post-mining land use options. An objective of the closure planning process is to prepare for the responsible transition of mine-affected lands to the agreed-upon long-term, post-closure land use. In jurisdictions like the United States, this may require returning the land to its ‘pre-mining’ conditions to enable and support pre-mining land uses (Poudyal et al., 2024), although this is not always possible.

Typically, post-mining transition does not occur until environmental and socio-economic risks have been addressed, and the overall risk profile of the site has been reduced to a level considered ALARP. As a result, a gap often emerges between the expectations of the post-closure state and the viability of transitioning the land to that expected state.

When closure criteria cannot be fully met, mining companies may retain the land title long after mining operations stop. In some cases–such as the Giant Mine in Northwest Territories and the Faro Mine in Yukon, Canada–the title transfers to the government, which must then manage the closed or abandoned mines in perpetuity (Government of Canada, 2024). This combination of uncertainty and history has resulted in a conservative approach to residual risk, with global examples of successful site relinquishment being a rare occurrence (Intergovernmental Forum, 2023).

Therefore, understanding and managing residual risk is critical for addressing the long-term liabilities that may persist at a mine site during closure and post-closure. Effective residual risk management helps facilitate sustainable land use that benefits the surrounding communities and ecosystems.

Understanding the Residual Risk Landscape Today

The starting point for identifying and evaluating residual risk is the risk assessment process and documentation that evolves throughout the life of mine. A detailed risk assessment identifies the various areas of the mine footprint, or domains, and evaluates their corresponding risk exposures. These risk exposures can be physical, chemical, environmental, or human health and safety-related.

For instance, if a recreational park is considered as the post-mining land use, the mine operator, in collaboration with regulators and stakeholders, is responsible for transitioning the land to a condition that supports parkland use. The challenge that arises is addressing what happens post-closure, when the operator steps away. Do they remain accountable for residual risks decades later, or does that responsibility transfer to the entity that ultimately manages the park?

The principle of ‘polluter pays’ forms the basis of the current approach to risk mitigation and liability (University of Victoria Environmental Law Centre, 2019). Under this principle, the mining company that benefits from the extracted resources is also liable and responsible for mitigating and managing the negative impacts of their operations. While progressive closure and final reclamation and remediation efforts can address most risk exposures, some residual risks remain as a liability for the mining company.

Governments, regulators, and other project stakeholders recognize residual risks as a significant challenge to post-mining transitions due to the lack of a consistent approach to identifying or managing unforeseen risks. Because the magnitude of residual risks can vary widely in scale, some stakeholders are often reluctant to assume responsibility and bear the cost for addressing and managing potential liabilities resulting from unforeseen events.

To address this, some jurisdictions have instituted funds that mining companies pay into during operations and at final closure. These funds have a dual purpose of remediating historically abandoned mines and providing pooled finance to address potential impacts from unforeseen risks of recently closed mines. These funds are managed under specific oversight by governments or government-appointed third-party financial institutions. These funds are designed to grow in value so as to be better positioned to address residual risks. Following the insurance mindset, it is anticipated that these risks are unlikely to manifest simultaneously. In this way, the pooled funds would provide the government with the benefits of risk-pooling.

To date, Canada has seen the relinquishment of one oil sands mine, one silica sands mine, and one uranium mine (Anderson, 2025; Ministry of Energy and Resources, 2018; Orano Group, n.d.). The latter two mines are currently managed by the Government of Saskatchewan under the Institutional Control Program. In other jurisdictions, one mine in each of Australia’s New South Wales and Queensland states, as well as one mine in New Zealand, have also been successfully relinquished to the government, along with one mine in Washington, United States (Anderson, 2025; Glencore, n.d.; Bowden et al., 2002; Caldwell et al., 2009). However, none of these sites have yet been transferred to a third party for post-closure land use (Bowden et al., 2002; Caldwell et al., 2009; Ministry of Energy and Resources, 2018).

Navigating the Complexities of Residual Risk Management

Defining residual risk can be challenging because risk acceptance and tolerance are subjective between rightsholders, community members, subject matter experts, and other project stakeholders. Differences in the vision for post-closure land use can lead to differing perspectives on acceptable risks. Even when there is an agreed-upon land use, the strategies and methods for remediation and reclamation can differ, with varying priorities for managing risks. This results in a lack of common language to guide strategies that provide the best value for the post-mining transition.

The decision-making time horizon also varies among the project stakeholders and those impacted by closure. Mining companies make decisions over several years, while governments may view the time horizon in which to evaluate impacts to be decades. Local communities may think generationally and the environment’s ability to respond can be even longer, requiring risks to be assessed over decades and potentially centuries. Therefore, an intergenerational and interdisciplinary conversation is required to identify potential risks as land and societal expectations evolve.

Since residual risks after closure are specific to each site, it is impractical to develop ‘one-size-fits-all’ mitigations and controls. This results in a lack of unified understanding of best practices for performing risk assessments across the mining industry. Furthermore, non-mining entities are unwilling and unable to take on undefined risks. The potential unknown costs to address undefined risks make governments and communities cautious about allowing mining companies to fully close out their liability.

Developing a Residual Risk Framework and Model: Research and Collaboration

There is a significant research gap in identifying, quantifying, and managing acceptable levels of residual risk, as well as understanding their transferability to a non-governmental third party. To better understand this gap, Okane is participating in a CRC TiME research project aimed at identifying best practices and developing effective risk transfer models.

One of CRC TiME’s recent initiatives focuses on developing a multi-criteria decision-making tool that integrates a range of perspectives and translates complex information into practical, actionable decisions.

Mine closure and residual risk management are complex challenges that require a diverse community of practice, including experts in engineering, environmental sciences, economics, actuarial sciences, community engagement, and legal. Interdisciplinary research requires engagement and collaboration from rightsholders, local communities, mining companies, government and regulatory bodies, and other project stakeholders. The greater the diversity of expertise, the higher the likelihood that most risks and uncertainties will be identified.

Our Approach

Sustainable mining is recognizing that mining is not the end of the land, but a transitional use of land. We must not only integrate closure planning and stakeholder engagement into the full mine lifecycle, but also develop a knowledge base focused on approaches, practices, and methods to identify, quantify, and manage residual risk for after operations.

CRC TiME is the first global research center dedicated to improving post-mining outcomes. As part of the Australian Government’s flagship Cooperative Research Centre Program, CRC TiME unites diverse partners to address the complex challenge of mine closure and post-mine transitions economically, socially, culturally, and environmentally. To learn more about CRC TiME, please go to https://crctime.com.au/enquire.

Okane is a Mining Equipment, Technology, and Service partner with CRC TiME, collaborating on a variety of projects. Guided by our purpose to “Help Create a Better Tomorrow”, we champion and specialize in an integrated approach to mine transitions and future land use.

We have global experience in developing residual risk management strategies that facilitate the identification of risks from various perspectives and address them effectively through adaptive management plans and trigger action response plans. Okane’s risk-based approach optimizes a mine’s project value while achieving positive environmental and social outcomes.

To learn more about Okane, please visit www.okaneconsultants.com or contact info@okaneconsultants.com.

Thank you to Sakshi Anderson and CRC TiME for their support and collaboration.

References

Anderson, S. H. (2025). Identifying, quantifying and managing acceptable levels of transferrable residual risk: A desktop study. Cooperative Research Centre for Transformations in Mining Economies (CRC TiME). CRC TiME Annual Forum 2025, Darwin, Australia.

Bowden, A. R., Lane, M. R., & Martin, J. H. (2002). Triple bottom line risk management: Enhancing profit, environmental performance, and community benefits. John Wiley & Sons.

Caldwell, J., Hutchison, I., & Frechette, R. (2009). The Cannon Mine tailings impoundment: A case history. University of Alberta Geotechnical Centre.

Glencore. (n.d.). Coal mine rehabilitation. Glencore. https://www.glencore.com.au/.rest/api/v1/documents/730cb55144476ac6a58eb283b8223697/GCAA_Rehabilitation-Info.pdf

Government of Canada. Office of the Auditor General of Canada. (2024). Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada: Contaminated sites in the North (Report No. 1). Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development. (2023). Relinquishment of closed mine sites: Policy steps for governments. Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development. https://www.igfmining.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/igf-jan-2024-rob-stevens-relinquishment-closed-mine-sites-policy-steps.pdf

Ministry of Energy and Resources. (2018). Post closure management of decommissioned mine/Mill properties located on Crown Land in Saskatchewan (Institutional Control Program). Government of Saskatchewan. https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/119330/RISADiscussionPaperDec2018.pdf

Poudyal, N. C., Gyawali, B. R., & Acharya, S. (2024). Reclamation satisfaction and post-mining land use potential in Central Appalachia, US. The Extractive Industries and Society, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2024.101550

University of Victoria Environmental Law Centre. (2019). Polluter pays. British Columbia (BC) Mining Law Reform. https://reformbcmining.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/BCMLR-Polluter-Pays.pdf